The first female calf born from sexed semen arrived in 1999, but the early product had some challenges regarding conception rates and uptake was slow. However recent advances in technology mean that for every one straw of conventional semen, four straws of the sexed product are sold, according to Cogent’s Andrew Holliday.

The conception rates of the initial sexed semen straws averaged 30% below that achieved by conventional semen, but technological developments have led to levels of 95%-plus and its results can easily match conventional success rates, as long as correct procedures are followed, says Mr Holliday, Cogent’s genetics manager.

Taking a conception rate of 100% for conventional semen, the performance of sexed semen currently averages 98-100%. This relative conception rate comparison is used as individual farm conception rates can vary widely from herd to herd, with some producers facing a fertility challenge and others achieving high pregnancy rate figures.

There were several other reasons why sexed semen failed to attract high numbers of sales in the years following its launch.

“It was expensive at first and the available bulls tended to fall within the second or third tier genetically,” he says. “This was because bull studs around the world were geared to marketing conventional semen. The best bulls were already selling out, with little stock available to convert to sexed semen. Another initial problem was that a reasonably high proportion of bull calves were being born to sexed semen. Cogent’s sexing procedure has since been refined and there is now a 90% chance of a female calf being born.

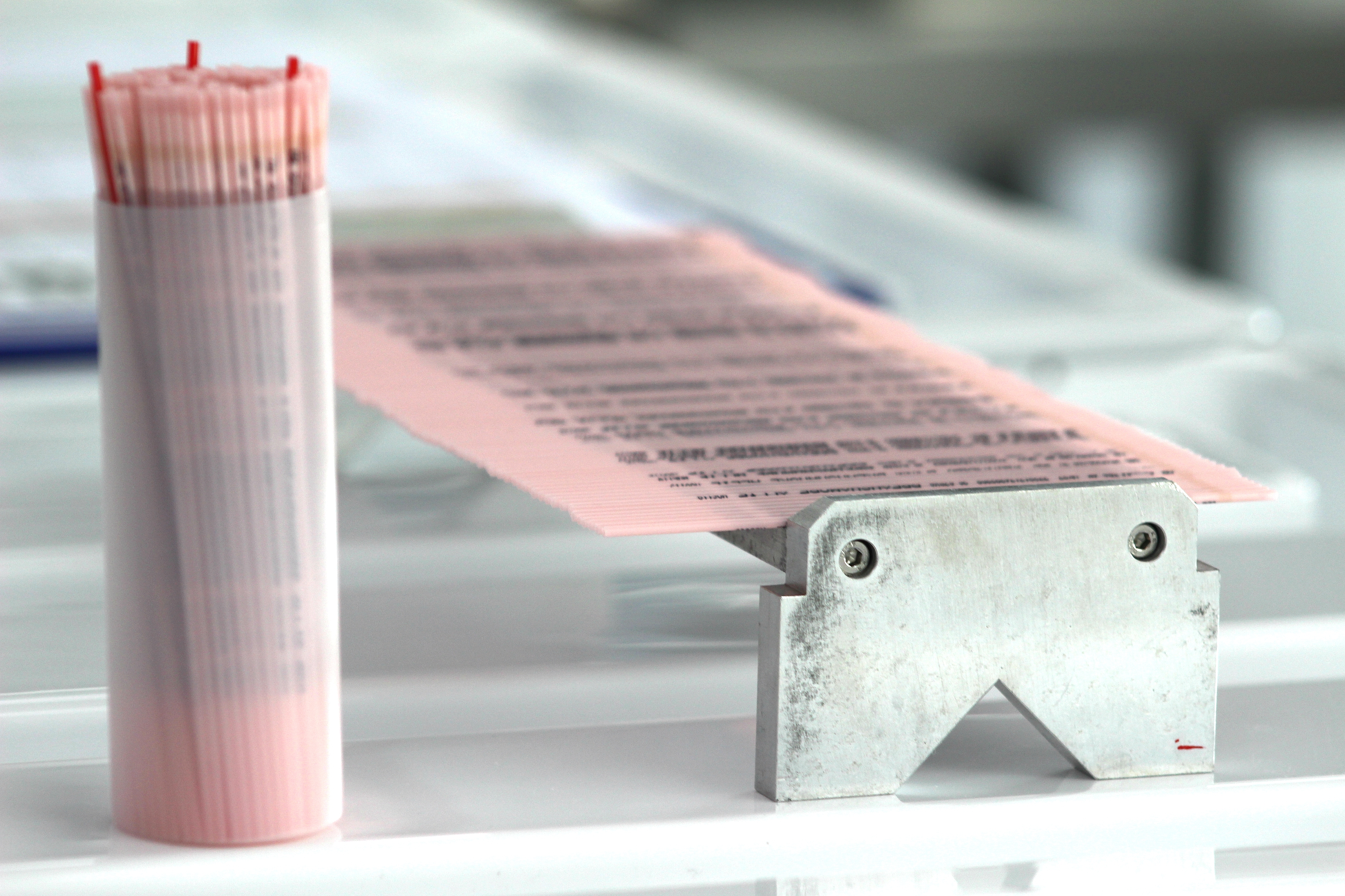

“But it does remain more expensive, compared with conventional, as there is a multi-step process involved and a lot of money has been invested in research and technology. In addition, sexed semen means that half of the semen has to be discarded. Sexed semen prices presently range from £26-£40/straw, while the conventional product costs £9-£20.”

The welfare issue linked to the production of dairy bull calves was one of the main drivers for its recent spike in popularity.

“Some of the milk buyers are stipulating practices for bull calves from the dairy herd, so producers have had little choice but to turn to sexed semen. The knock-on effect in a rise in beef bull semen and around 50% of our sales are for beef bull straws.

“A 200-cow dairy herd, for example, would require an average 50 heifers each year. This leaves three-quarters of the herd free to put to a high quality beef bull. Natural service with dairy bulls has been in rapid decline over the past couple of decades and it is now a rarity on dairy units. When bulls are used, they are generally confined to sweeping up.”

The practice of using sexed semen has been adopted across all types of production systems, but it may be considered particularly appropriate to block-calving herds, where an influx of dairy bull calves may be especially unwelcome, he adds.

He explains why sexed semen conception rates have historically been lower, compared with the conventional product and why the timing of insemination is more critical.

“Capacitation is the process the sperm cell undergoes before it has the ability to fertilise an egg. This process starts from the moment that sperm cell leaves the testicles of the bull, which means that the time an ejaculate is processing in the lab before it is frozen is highly relevant, he says. “Conventional semen is frozen within a very short time after collection, but due to the 10-12 hour processing that is required for sexed semen, it means those sperm cells are much further down the path of development and there for has a shorter window for successful insemination.

“The insemination procedure for sexed semen differs little from conventional, but females should be served slightly later during the heat period; we recommend 18-24 hours after the onset of heat. If this advice is not observed, it is the only factor that can have a negative effect on conception rates. Our research shows that the calves-born figures for both products is equal. ”

“As sexing semen is a more expensive process, there was a general industry practice of including relatively low numbers of sperm for each straw. We have recently increased the number of sexed sperm cells per straw from 2 million to 4 million and this together with our advancements in sorter technology and new sperm cell medias has lifted conception rates now to a point where Sexed ULTRA 4M is rivalling conventional semen.

One of the reasons for the high pregnancy rates through sexed semen was because it was generally used on heifers, admits Mr Holliday. Nevertheless, many Cogent clients achieved good results on second and third calvers. It had been widely taken up by pedigree breeders, but he advised its use to be limited to younger animals, to speed up genetic progress. An older cow was perceived to have good breeding potential due to its high yields, but it would not be a good long-term policy for improving the herd as a whole; sexed semen should be reserved for the “genetically elite,” he says.